Oklahoma task force looks to resolve tribal reservation safety issues without tribal nations

by Molly Young, The Oklahoman

A task force launched by Gov. Kevin Stitt will attempt to create a standard working agreement for state and tribal public safety agencies, but without any say from tribal leaders, at least for now.

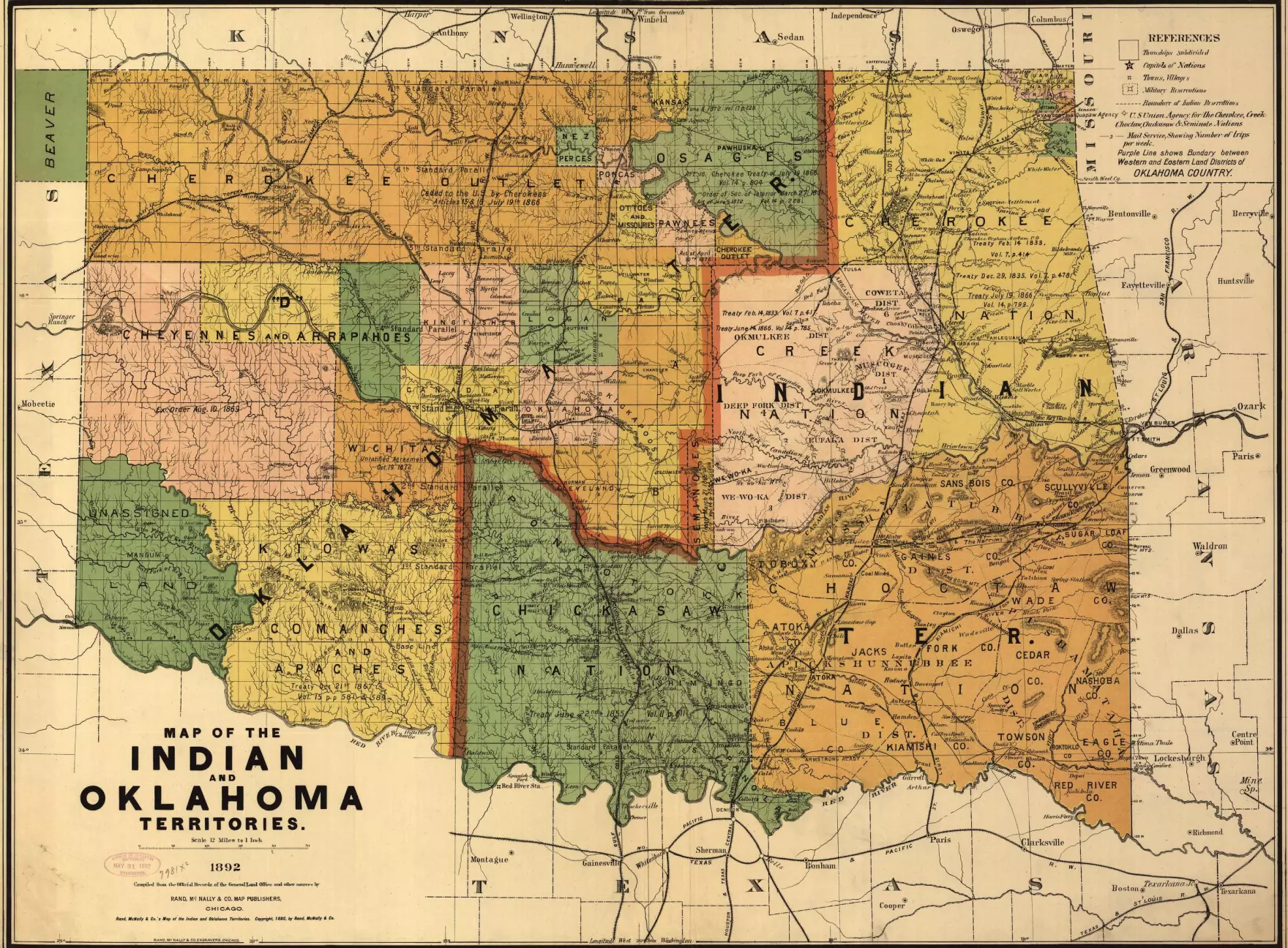

Tricia Everest, Oklahoma’s public safety secretary, said at a task force meeting Monday that she doesn’t believe Congress will resolve any questions about policing powers that stem from McGirt v. Oklahoma, a landmark 2020 Supreme Court decision. The ruling has led to the recognition of nine tribal reservations in the eastern half of the state — and drawn constant ire from Stitt because states have limited power over tribal citizens on tribal lands.

He created the One Oklahoma Task Force in December to address the “havoc” caused by the ruling and appointed Everest as the group’s chair. He asked the group to come up with a range of potential fixes, including possible changes to federal law. Everest said legislation appears unlikely, however.

“I was told that Congress in no way, shape or form is going to touch any of this,” she said.

She proposed updating an existing federal law enforcement agreement to match the day-to-day realities of policing tribal areas. The new document would spell out how cities, counties and state agencies work with tribal nations to keep all people safe.

The task force talked about Everest’s proposal for the first time Monday. But at one point, Sen. Jessica Garvin, R-Duncan, paused the discussion to ask about the most notable absences from the meeting.

“There may be some tribal leadership in here that I’m not —”

“There’s not,” Everest interjected.

“OK, so do we even know that they’re going to be amenable to signing something new?” Garvin said. “I mean if they’re not in the room — ”

Everest, sitting in front of a portrait of the Cherokee linguist Sequoyah, said whether or not tribal leaders are present, they would always have a seat at the table.

Why leaders of the Five Tribes opted out of Gov. Kevin Stitt's task force

Criticism over the lack of tribal representation has permeated the task force for months, ever since the governor created the group and assigned two spots to be shared among the 39 tribal nations based in Oklahoma. Many tribal officials decided to boycott the task force in response.

Leaders of the Five Tribes officially opted out, raising concerns about the group’s makeup and intent.

“What we cannot do is participate in an effort that spreads falsehoods about the law, attempts to minimize tribal voices and engages in political attacks instead of constructive government-to-government dialogue,” the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee and Seminole nations said in a January letter to Stitt.

Jack Thorp, a district attorney in northeast Oklahoma who sits on the task force, said he believes tribal leaders would be open to talking through problems and finding solutions. He pointed to a conversation he had earlier this month with Cherokee Nation attorney general Chad Harsha about common concerns in their region.

Thorp also pointed to the fact that tribal nations worked out dozens of agreements with law enforcement agencies soon after the McGirt decision. He said those agreements have worked for all agencies.

“From their standpoint, they need city, county, state law enforcement to police their reservations, and so it works back and forth for that,” Thorp said. “So they’re generally pretty agreeable. I think absent, maybe just, if we get up to Oklahoma City-type fights.”

Everest said she did not want to try to update every agreement that already exists, but instead create a new umbrella agreement that agencies could use. She suggested several changes to a 2005 model agreement created by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and created a pair of working groups to come up with detailed suggestions on how to update the wording.

As one idea, she proposed adding a section to reimburse agencies that provide extra officers at the request of tribal nations.

Jason Chennault, the Cherokee County sheriff, pushed back against the suggestion, saying he didn’t like it a bit.

“As long as our Native Americans are still paying taxes, they’re paying us,” Chennault said.

One of the biggest discussion points was making sure officers do not face the potential of being sued for responding to calls involving Native Americans.

Department of Public Safety Commissioner Tim Tipton said the possibility weighs on troopers’ minds in heated situations.

“I don't know how to clear that all up,” Tipton said. “I don't even know if, from a state standpoint, if we can bring more clarity.”

The task force will next meet April 1 and has until June 1 to deliver its recommendations to the governor.

Tipton and others said education and training will be the key to whatever the group ultimately decides, so officers writing tickets and responding to calls know how the McGirt decision affects them. There’s a lot of uncertainty now, said John Weber, a Sallisaw police officer who is representing the Oklahoma State Fraternal Order of Police on the task force.

“If you go to talk to 13 different counties and 13 different cities, they’re doing 13 different things,” he said.

Molly Young covers Indigenous affairs. Reach her at mollyyoung@gannett.com or 405-347-3534.

Enrollment in tribal language courses grows in Oklahoma as tribes aim to increase fluency

The number of students taking tribal languages has grown by the thousands in public schools

OKLAHOMA CITY — Like many Cherokee Nation citizens of his generation, Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. never had the chance to learn his tribal language in school.

He said those opportunities simply didn’t exist at the time.

“It would have meant a great deal to me,” Hoskin said. “It would have meant the opportunity to learn the Cherokee language as a child.”

Today’s generation of children has more possibilities, he said. State data shows an increasing number of students are seizing the chance.

Enrollment in Native American language programs is growing in Oklahoma public schools, according to information from the state Department of Education.

At least 3,314 students, from elementary through high school, participated in an Indigenous language program at their public school in the 2022-23 school year. That’s over 1,000 more students than the previous school year and 2,500 more than in 2020-21, according to state data.

Last year’s total includes about 1,600 elementary and middle school students who participated in Indigenous language programs.

Another 1,700 students earned high school world language credits by taking Choctaw, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Comanche, Mvskoke, Osage, Pawnee, Potawatomi, the Otoe-Missouria language of Jiwere-Nat’Chi, and other courses. The right to take an Indigenous language for high school credit was encoded in state law in 2014.

Choctaw and Cherokee classes had the most participating students and were offered in the greatest number of schools, according to the state Education Department.

The Cherokee Nation aims to grow its numbers with plans for a $30 million language immersion middle school. The investment would expand the capacity of its existing immersion middle school that teaches in the Cherokee tongue.

The tribal nation has pledged to spend at least $18 million a year on various language-preservation initiatives.

“We know we’ve got people on the way to fluency in what is a very difficult language to learn,” Hoskin said. “We just need to have more of them, given what we’re up against.”

The Cherokee language has 2,000 first-language speakers and thousands more at a beginner or proficient level.

UNESCO labels Cherokee as a language in danger of extinction. Chickasaw, Choctaw, Comanche, Potawatomi and other tribal languages found in Oklahoma also are designated as endangered.

Generations of Indigenous children were discouraged or forbidden from speaking their tribal languages at federally run boarding schools across the country for 150 years, according to a 2022 report from the U.S. Department of the Interior.

The boarding schools existed to culturally assimilate Native American children, and Oklahoma had more of these schools than any other state, the report found.

Tribal nations are now working to rebuild their ranks of fluent speakers.

The Choctaw Nation, for example, has its language taught in the greatest number of high schools in Oklahoma, as well as at colleges, early childhood centers, community classes and online. Fifteen adults are taking Choctaw as a full-time job through the tribal nation’s apprenticeship program.

Many Native American languages have a high degree of difficulty for English speakers to learn, according to state academic standards.

Cherokee, for instance, is a Class IV language, indicating it would take a similar number of hours to gain proficiency as it would to learn Greek, Hebrew or Russian. Languages more similar to English — like Spanish, Swedish and French — would take fewer hours of study to reach the same proficiency level.

Indigenous language courses must be sanctioned by the state Education Department for students to earn class credit.

In most public schools, the language teachers and lesson plans come from tribal nations, said Jackie White, the state agency’s program director of American Indian education.

“We wanted to make sure, whomever taught, that they were fluent speakers and that what they taught was credible,” White said.

White joined the agency in 2020. Since then, the department has expanded its Native American education staff, helping to boost communication between tribes, schools and the agency about Indigenous-focused programs.

Those conversations have included expanding tribal language courses to more schools through both in-person instruction and online teaching, White said.

Bartlesville High School is among the schools to recently add a face-to-face Indigenous language course. Only minutes away from the Osage Reservation, the northeast Oklahoma school is in its third year offering Osage language classes.

The school has 35 students enrolled in Osage I and 27 in Osage II, said Principal Michael Harp. He said the courses have attracted a diverse group of students, not only those who are Native American.

Interest in Indigenous culture has grown, he said, especially with movie filming of “Killers of the Flower Moon” taking place in the Bartlesville area.

“There definitely has been an uptick in the last couple of years of just students wanting to know more about their heritage, the culture (and) the culture that is around them,” Harp said.

Oklahoma court recognizes Wyandotte Reservation, criminal jurisdiction

The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals has recognized that the Wyandotte Reservation was never disestablished.

By Graycen Wheeler, KOSU

The Wyandotte Reservation was founded in Northeast Oklahoma in 1867, after the tribe’s members were forcibly removed from the upper Midwest.

Steven Leon Fuller was charged with driving under the influence of alcohol on Wyandotte land in 2022 but appealed his conviction. As a Cherokee Citizen, Fuller argued the DUI should be under tribal or federal jurisdiction, not the state’s.

That appeal hinges on the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2020 McGirt v. Oklahoma decision, which affirmed the Muscogee Nation’s reservation was never disestablished, and its lands remain under tribal jurisdiction.

Last week, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed that the Wyandotte Reservation was never disestablished.

“The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals[...] affirmed what we already knew to be true: the Wyandotte Reservation — the seat of our government and the land on which our Ancestors sought refuge and created a home — continues to exist,” Wyandotte Chief Billy Friend said in a statement.

Wyandotte is the ninth tribal reservation to have its continuous existence recognized in Oklahoma post-McGirt. A total of 37 federally recognized tribal nations have land in Oklahoma.

Jacobson House Hosts “Collective Wisdom” Traveling Exhibit

NORMAN — Indigenous values of community, collaboration and shared experience take center stage when the traveling art exhibition, “Collective Wisdom,” goes on display at the Jacobson House Native Art Center. The show opens at 6 p.m. Friday, April 5 at 609 Chautauqua in Norman.

The show features 31 artists, and each item in the exhibit is a collaboration. The collection includes both two- and three-dimensional art and incorporates figurative, abstract, and traditional Native styles.

The participants in the exhibit include many award-winning Native artists, who are predominantly from Oklahoma tribal nations. These include Marcus Amerman, Choctaw; Marwin Begaye, Navajo; Roy Boney, Cherokee; Chance Brown, Chickasaw; Amber Dubois-Shepherd, Navajo/Prairie Band Potawatomi/Sac and Fox; Tom Farris, Otoe-Missouria/Cherokee; Kristin Gentry, Choctaw; Brent Greenwood, Chickasaw/Ponca; Kennetha Greenwood, Otoe-Missouria; Billy Hensley, Chickasaw; Karma Henry, Paiute; Joshua D. Hinson (Lokosh), Chickasaw; Tyson Hudson, Chickasaw; Brenda Kingery, Chickasaw; Dustin Mater, Chickasaw; Natalie Miller, Chickasaw; Cotie Poe-Underwood, Chickasaw; Stuart Sampson, Citizen Band Potawatomi; Candace Shanholtzer, Choctaw; Erin Shaw, Chickasaw/Choctaw; Hoka Skenandore, Oneida/Oglala Lakota/La Jolla Band of Luiseno/Chicano; Nathalie Standingcloud, Cherokee; Jerry Sutton, Cherokee; Kindra Swafford, Cherokee; Deana Ward, Choctaw; Bryan Waytula, Cherokee; Micah Wesley, Kiowa/Mvskoke; Margaret Wheeler, Chickasaw; Dean Wyatt, Cherokee; Summer Zah, Dine/Choctaw/Jicarilla Apache.

The opening will also honor the work and lifetime contributions of Caddo/Potawatomi artist Jeraldine “Jeri” Redcorn. Recognized both nationally and internationally for reviving Caddo Pottery, Redcorn was inducted into the prestigious American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2021. President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama selected Redcorn’s art for display in the Oval Office, and the First Americans Museum in Oklahoma City displays her art and honored her for the first Native Creative Artist Award. Her work is on permanent display at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, the Oklahoma Museum of History, Oklahoma State Supreme Court, Louisiana State Museum, Spiro Mounds and the Texas State Natural History Museum. With goals that focus on humanitarian and environmental issues, Redcorn commits to purposeful activism seeking tolerance, understanding, sharing and acceptance.

“I am proud to be honored as a Jacobson House founding member, saving this historic home from becoming a parking lot,” Red Corn said. “My husband Charles Red Corn and his brother, Jim Red Corn, met with Dr. Oscar Jacobson to discuss art when they attended OU. (Both Charles and Jim are deceased.) My passion is Caddo history, art, language, songs, dances of our people and continuing our ways.”

An invited guest of the Collective Wisdom reception who will honor Redcorn alongside the Jacobson House board members is Osage tribal member Scott George, whose song “Wahzhazhe (A Song for My People)” from the film Killers of the Flower Moon is an Oscar nominee for “Best Original Song.” Redcorn’s husband, the late Charles Red Corn, also wrote a novel based on the Osage murders, A Pipe for February, and her son, Yancey Red Corn, is part of the Killers of the Flower Moon cast.

“We are excited to host this exhibition of some of our most prominent and emerging Oklahoma First American artists,” said Oscar Jacobson Foundation Chair Brent Greenwood. “Without the founding board members Jeri and the late Charles Redcorn, along Carol and the late Dave Whitney, we would not have this historic house to host such an exhibition. With gratitude, none of this would have been possible without our Jacobson House supporters, the Norman and University of Oklahoma community and the Board of Trustees’ servant leadership.”

The exhibition will show through Friday, August 2, and opening reception is free and open to the public. Art in the Collective Wisdom exhibition is also available for purchase. For more information, call the Jacobson House Native Art Center at 405-706-1101 or visit www.jacobsonhouse.art.