This long-running lawsuit is the latest dispute over Oklahoma tribal relations

by Molly Young

Oklahoma Attorney General Gentner Drummond wants to take the lead in representing the state in a long-running tribal gaming lawsuit. But Gov. Kevin Stitt’s office says he has no plans to hand over the reins.

Drummond called defending the federal suit a “waste of state resources” and asked for approval to enter the ring and end the case in a June 16 letter to legislative leaders. Stitt’s general counsel told lawmakers in his own July 11 letter that Drummond has no standing.

The legal dispute is the latest clash among Oklahoma’s top elected officials over tribal relations.

Stitt has had rocky relationships with many tribal governments since 2019, when he challenged the central state-tribal gaming compact as unfair. Drummond took office in January and has often split from Stitt on key issues involving tribes, which he has described as economic engines for the state.

Both contend their approach to the federal lawsuit is what’s best for Oklahoma.

What to know about the case, and the gaming compacts in Oklahoma

The case currently centers on the legal standing of standalone gaming compacts the governor negotiated with the Comanche and Otoe-Missouria nations. Four other tribes with sizable gaming arms — the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw and Citizen Potawatomi nations — sued in 2020 to stop the agreements from taking effect outside the model gaming compact.

The model gaming compact sets the framework for Las Vegas-style gaming in Oklahoma and gives tribes exclusive rights to operate those facilities in exchange for paying the state a specific cut of revenues. Oklahoma collected $200 million through the agreement from May 2022 through April.

Oklahoma’s highest court ruled the outside compacts signed by Stitt were invalid. Federal gaming regulators did not directly reject the deals, though, which has prompted the legal fight over their future.

The governor clearly acted outside state law when he signed the deals on behalf of the state, Drummond said in his letter. “The Oklahoma Legislature did not approve of or authorize Governor Stitt to bind Oklahoma to these compacts,” Drummond wrote.

His letter to lawmakers was first reported by the online news outlet NonDoc and later provided to The Oklahoman by the attorney general’s office. It was addressed to House Speaker Charles McCall and Senate President Pro Tem Greg Treat. Drummond wrote that he believed legislative sign-off would give him the strongest argument to enter the case on Oklahoma’s behalf.

More:A law pressured tribes to give up land in 1898. It doesn't give Tulsa power today, court rules

McCall replied June 26, saying the attorney general already has the power needed to enter the case. “If you, as attorney general, deem it in the best interest of the state of Oklahoma for you to intercede in this litigation, then I and the citizens would expect you to do so,” McCall wrote. “The House will not interfere in that decision.”

A spokesperson for Treat said he is still reviewing the attorney general’s letter, as well as the July 11 response from Stitt’s attorney, Trevor Pemberton.

Oklahoma’s attorney general cannot “unilaterally assume representation of the governor,” Pemberton wrote. He said professional conduct rules and legal precedence bar Drummond from doing so.

“The Oklahoma Supreme Court long ago made clear that, where the governor and the attorney general are at odds over a litigation objective, the governor’s decision prevails under the state’s constitutional framework,” Pemberton wrote in the letter, which the governor’s office provided to The Oklahoman. A spokesperson for the governor declined to comment further on the legal dispute.

More:McGirt v. Oklahoma, 3 years later: How police work on the Muscogee Nation reservation

In his letter, Pemberton pushed back against Drummond’s description of the lawsuit as protracted, noting that the tribal nations who sued could end the proceedings by dropping the case. He also contested Drummond’s assertion that the governor has hired “several Washington, D.C. and New York City law firms” to defend the case.

Pemberton said one such law firm is now leading the case with help from lawyers from a second law firm in Oklahoma City. Court records show the local firm is Ryan Whaley.

In response to Pemberton’s letter, Drummond said he is not trying to represent Stitt, but the state, to end a costly legal fight. “The Oklahoma Supreme Court has issued two opinions that make it clear the governor had no authority to enter into the compacts he is seeking to enforce,” the attorney general’s office said in a written statement.

Drummond has not said if he will move to enter the case without the formal legislative approval he requested. A spokesperson for McCall said his stance is unchanged after receiving Pemberton’s letter.

A different compact dispute is front and center for lawmakers. The Legislature passed a pair of bills in May to renew the state’s tobacco and car tag compacts with tribal nations through 2024. Stitt vetoed the measures in June. The Senate’s first veto override vote failed. Senators plan to vote again July 24.

More:What tribal leaders in Oklahoma are saying about a key Supreme Court decision

Molly Young covers Indigenous affairs. Reach her at mollyyoung@gannett.com or 405-347-3534.

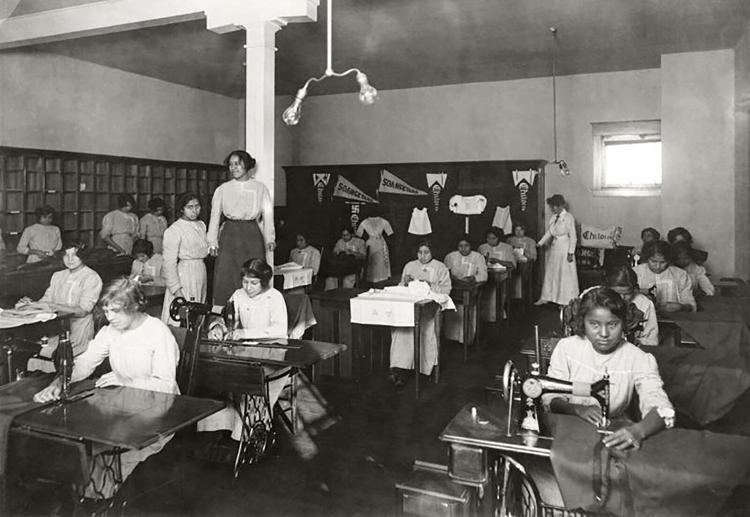

American Indian boarding schools in Oklahoma workshop is Aug. 5

OKLAHOMA CITY – The Oklahoma History Center will host a workshop on Saturday, Aug. 5 that focuses on American Indian boarding schools in Oklahoma.

A 2022 report from the US Department of the Interior detailed the assimilationist policies and inherent abuse that the schools employed for decades. The report identified more than 400 schools across 37 states that operated between 1819 and 1969, including 76 in Oklahoma.

From 10-11:30 a.m., Dr. Farina King (Diné) will give an overview of the history of American Indian boarding schools in the state through a spatial lens while building on her work with the “Mapping Tahlequah History” project at Northeastern State University. This project demonstrates the value of citizen-led history to historical analysis.

From 12:30-2 p.m., Oklahoma Historical Society archivist Mallory Covington will provide an overview of the American Indian records at the OHS with an emphasis on documents relating to Indian boarding schools.

The sessions with King and Covington are open to researchers, students, educators and the general public.

A session for educators only will take place from 2-3:30 p.m. It will focus on bringing this topic into the classroom and connecting it to social studies standards OKH 5.1, WG.3.3 and USH.1.3.

The sessions will be available in-person at the Oklahoma History Center and virtually via Microsoft Teams. The workshop is free, but registration is required. A lunch break will take place from 11:30-12:30 p.m., but lunch is not provided. Those attending virtually will receive a confirmation email with a link before the event.

Dr. Farina King is Bilagáanaa (English American), born for Kinyaa’áanii (the Towering House Clan) of the Diné (Navajo). King is the Horizon Chair in Native American Ecology and Culture and associate professor of Native American studies at the University of Oklahoma. Between 2016 and 2022, she was an associate professor of history at Northeastern State University in Tahlequah. She was also an affiliate of the Cherokee and Indigenous Studies Department and the director of the NSU Center for Indigenous Community Engagement. She is a past president of the Southwest Oral History Association.

Mallory Covington attended the University of Central Oklahoma, where she graduated in 2010 with a master’s degree in Museum Studies. She started with the Oklahoma Historical Society in 2011, working on a newspaper digitization project for “The Gateway to Oklahoma History” and cataloging oral history. During that time, she also worked in photos, maps, registration and cataloging film and video. In 2013, she moved to the manuscripts department and, in 2017, became a certified archivist. In 2019, she became the Archival Collections Manager.

The Oklahoma History Center is located at 800 Nazih Zuhdi Dr. in Oklahoma City. It is open to the public from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday through Saturday. Call 405-522-0765 or visit www.okhistory.org/historycenter for admission costs and group rates.

Choctaw Nation Partners with Oklahoma State University Institute of Technology for Culinary Program

Choctaw Nation employees to receive hands-on culinary training, course credit

DURANT, Okla. – In a one-of-a-kind partnership, Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma (CNO) Division of Commerce is teaming up with Oklahoma State University Institute of Technology (OSUIT) to offer Choctaw Casinos & Resorts food and beverage associates culinary training and college course credit beginning July 17.

Choctaw Nation and OSU Institute of Technology have created an educational course designed specifically for casino and resort associates that’s aimed at preparing them for culinary careers. If associates decide to pursue further accreditation, certification, or degree programs with OSUIT, they will receive prior learning credit toward their educational goals. Choctaw Nation casinos are the first to implement a program of this nature in Oklahoma.

“We’re thrilled to offer our associates an opportunity to kick-start their careers,” Heidi Grant, Choctaw Nation Executive Officer of Gaming and Hospitality, said. “Our goal is to empower each associate with the knowledge to succeed in their new adventure. Whether they are working toward an Associate’s Degree in Applied Science in Culinary Arts or seeking a certificate, we are laying a foundation they can build upon.”

Prior to starting their new roles at one of Choctaw Casinos & Resorts’ 42 restaurants, new associates will receive a week of virtual and hands-on learning through OSUIT culinary training program to help get them acclimated in their new role.

Each day begins with training videos and quizzes before moving into hands-on preparation and one-on-one attention from qualified Chef instructors. The first week ranges from the basics of hygiene and kitchen safety to detailed instruction on cooking methods.

After week one, employees will transition to their work locations to continue learning. Ten weeks later, they will begin taking in-depth courses in the second-tier level of training, which includes advanced cooking skills, techniques, and terminology. At the end of second-tier training, associates will be able to prepare a two-course meal and receive a co-branded CNO and OSUIT certificate.

This program will also be available to existing culinary team members who wish to sharpen their skills. Some current associates may be scheduled to attend training as a refresher, but all are able to utilize the training by coordinating with their supervisor.

If you’re interested in a culinary career, check out Choctaw Casinos & Resorts food and beverages opportunities here.

Boiling Springs Church hosts bell dedication ceremony

It started out as a Boiling Springs Church reunion.

Haskell Alexander, a Chickasaw citizen and longtime church attendee, said the church, located near Allen, Oklahoma, had not hosted a reunion since well before the COVID-19 pandemic.

While the reunion was being planned, former church congregant Gary Dean Johnson and his son, Chad, decided to donate a new bell, which has been a missing reminder of a simpler time, as well as a hallmark of Chickasaw community involvement. Boiling Springs Church is one of the churches continuing today that were part of the Seeley Chapel movement.

“There is much history behind that first annual meeting at Seeley Chapel six decades ago,” said Chickasaw Nation Governor Bill Anoatubby in his 2020 State of the Nation address at the Chickasaw Annual Meeting and Festival. “During that time, churches like High Hill, Boiling Springs, Johnsons’ Chapel, Yellow Springs, Sandy Baptist, Sandy Creek, Red Springs, Pennington and, of course, Seeley Chapel – these were the epicenters of tribal communication.”

History of Boiling Springs Church

Along with these other churches in the Chickasaw Nation, Boiling Springs Church is an important and living part of Chickasaw history and culture. The church was named after the fresh springs that bubbled or “boiled” up from the ground.

According to a marker at the church, it was built in 1911 when missionaries spoke to Chickasaws in the area about constructing a church. The marker states members of the Frazier and Burris families got money for the land the church was eventually built on by chopping cotton.

“Descendants of those families still attend and support the church, which continues to be a center for the Chickasaw language,” the marker says.

The Rev. Jefferson Davis “Sonny” Frazier and the Rev. Jesse Humes, both inductees of the Chickasaw Hall of Fame, were descendants of the original families and both served as the church’s pastors. Stanley Smith, who was a master language teacher for the Chickasaw Nation and recipient of the Chickasaw Nation Silver Feather Award in 2007, also served as pastor of Boiling Springs Church.

Alexander said he is a descendant of the Frazier family.

“At that time when the church started, everyone spoke Chickasaw and Choctaw,” Alexander said. “We still sing the Choctaw hymns there today.”

Mary Smith, a Chickasaw citizen, wife of Stanley Smith, longtime church attendee and descendant of the Frazier family, said she learned to sing Choctaw hymns from her father.

“When I was 9 or 10, I would be in the back seat, and my dad would start singing our hymns,” she said. “That’s how I learned Choctaw hymns.”

She often leads songs at the church and sings at funerals. After a stroke in 2016, Smith said she thought she wouldn’t be able to sing the hymns anymore.

“I never thought I’d be able to talk or sing again,” she said, her voice beginning to shake. “But I’m so glad God restored my voice. That’s why it’s important to me to sing our songs.”

Alexander said many descendants of these families, some who have since moved away, return to attend the church during Easter, Christmas and special gatherings.

“We enjoy our special holidays and gatherings, because they do come back and share memories,” Alexander said.

In addition to being a place to worship and learn about God, the church served as the site of important political events for the Chickasaw Nation after Removal to Indian Territory.

“In the late 1840s, Chickasaw leaders met at Boiling Springs to begin drafting the constitution and first laws of our nation,” said Governor Anoatubby in a speech to the Oklahoma Indian Missionary Conference in 2011.

It was among other Chickasaw churches important to the 1950s and 1960s grassroots Seeley Chapel movement which saw Chickasaws gather to help restore the recognition of Chickasaw sovereignty and self-government.

In large part because of this movement, in 1971, the Chickasaw Nation elected Overton James during its first election for tribal governor since Oklahoma statehood in 1907.

Alexander said the church bell called people in the community together, and congregants were involved in their community and their tribe.

“That was basically where people got their information, at the churches,” he said. “That was where everyone got their news about the Chickasaw Nation.”

“The bell meant a lot to the Chickasaw people,” said Smith. “When it was time to start, all they had to do was ring the bell, and people knew it was time for church.”

According to Alexander, the Boiling Springs community was large and lively, and there were 21 children who got on and off the school bus at a single stop there.

“The kids would almost fill up half the bus right there at that one stop,” he said. “It was always a lively place, and that was one reason for the church bell.”

Alexander said his grandfather, Jeff Alexander, began attending church at Boiling Springs in the 1930s and was at one point a deacon of the church.

“He rang the church bell many times,” he said.

Boiling Springs Church was the site of the second Chickasaw Church Tour during the Chickasaw Annual Meeting and Festival in 2018, a yearly tour of the churches that have served as important political and cultural sites for the Chickasaw people.

“Our churches are where we gathered. It’s where we gained strength and spiritual insight,” said Chickasaw Nation Legislator Lisa Johnson-Billy about the Chickasaw Church Tour.

At some point around 1990, Smith said the church bell was stolen.

“One Sunday we came to church, and it was gone,” she said. “It was a big bell. It would take a lot of guys to handle that.”

After learning who might have the bell and requesting that it be returned, Smith said it was eventually placed back by the church gate, and church leadership stored it in the church’s camp house. Before it could be hung, however, it was stolen again.

Reunion and bell dedication

When the Johnsons, who are also descendants of the Frazier family, decided to donate a new bell for the church, the church reunion of congregants and descendants of the Chickasaws who founded the church took on a new significance.

Alexander said he believes it is important to continue the tradition of coming together in service to the Lord and each other.

“I truly believe we have to keep it going,” he said. “It’s very important in our lives. Times have changed a lot.”

Smith said she’s glad to be a part of the legacy of the Frazier family and the Boiling Springs Church.

“I am so proud that my dad and my grampa taught us a lot,” she said. “The church is so important to us now.”

April 30, 2023, Boiling Springs Church hosted a reunion and bell dedication ceremony. Alexander said Johnson-Billy shared the sermon. Phillip Billy led worship in song, and Choctaw hymns were sung as they have been in years past.

Following the service, Alexander said Gary Dean and Chad Johnson were the first to ring the new bell.