The House Subcommittee on Indian and Insular Affairs met last week to discuss and debate two pieces of legislation that could change the way land leases are handled in Indian Country.

The bipartisan HR 1246 authorizes land leases of up to 99 years for land held in trust for federally recognized tribes, while HR 1532 explicitly states that tribes may lease, sell, convey, warrant, or otherwise transfer real property situated on fee — i.e. not trust — lands owned by said tribe without the opinion or approval of the federal government.

Committee Chair Harriet Hageman (R-Wyo.), who sponsored both bills, said the two bills, in tandem, would help “unlock economic potential” in Native communities where land-leasing issues have long stymied economic development and job creation.

“We should ensure that Indian Lands, whether owned as fee or restricted fee lands, or held in trust for the benefit of the tribes are able to be used as tribes want to use them,” Hageman told the committee during her opening statement. “I believe these bills are a good step forward to ensure that.”

Minority Chair Raul Grijalva (D-Ariz.,) a co-sponsor of HR 1246, echoed Hagerman’s sentiment, calling the bills a method of “addressing barriers” to economic development, as well as “paternalism” on behalf of the federal government.

“[We’re] amplifying tribal self-determination and the issue of sovereignty for federally recognized tribes,” Grijalva said. “This is a very important step.”

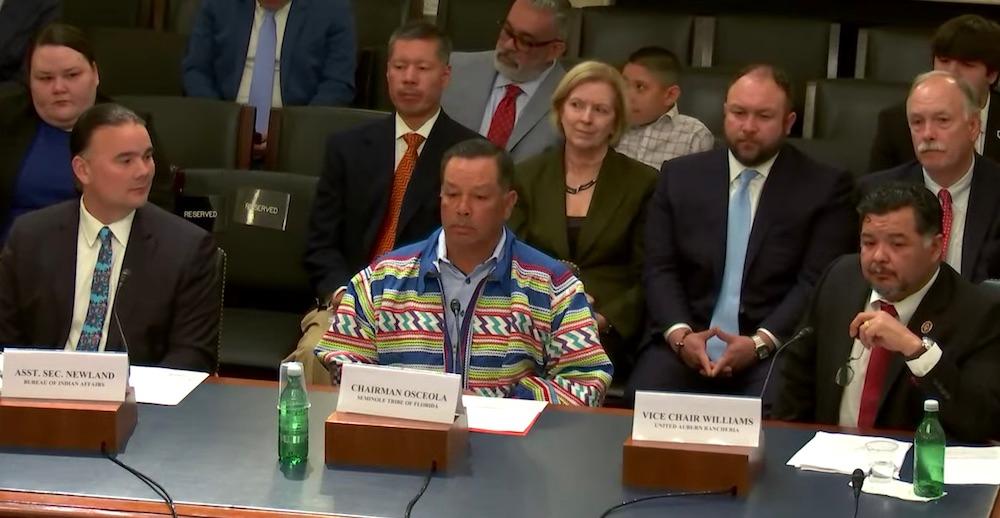

The committee also invited a number of witnesses for input on the bills: Department of Interior Assistant Secretary-Indian Affairs Bryan Newland, Seminole Tribe of Florida Tribal Council Chair Marcellus Osecola Jr., and United Auburn Rancheria Vice Chair John Williams.

Long term leases see broad support

Newland expressed the BIA’s broad support for HR 1246 as a way to sidestep increasingly onerous use of the 1955 Long Term Leasing Act, which requires an act of Congress to add new tribes to the list of qualified leasers.

So far that list includes 60 of the country’s 574 federally recognized tribes. The remainder must instead seek approval from the Bureau of Indian Affairs to lease trust land for 25 years, with an optional second 25-year term. Per Hagerman, many businesses and aspiring entrepreneurs don’t see a use-case for short lease terms, and that pulls business away from tribal communities.

“We trust the tribes to make the right decisions for their own people. Congress has amended the Long Term Leasing Act more than 50 times to adjust the terms and conditions of leases of Indian lands,” Hagerman said. “It's time to end this piecemeal approach of the past 67 years. By proactively extending this authority to all federally recognized tribes, economic development plans can proceed on a more expedited path.”

Newland testified that the current process frequently holds up tribal economic development plans as new bills work their way through Congress and into law. Amending that process to allow federally recognized tribes universal access to 99-year leases would allow for more agile development, he told the committee.

“The Department supports the goal of this legislation as it would promote economic development opportunities and avoid tribes having to acquire separate legislation for this purpose,” Newland said.

Non-intercourse creates frequent intervention

Much of the hour-long hearing concerned itself with HR 1532, which Osecola and Williams both pushed for passage, while Newland expressed the BIA’s opposition to the bill.

The bill would interact with the Indian Nonintercourse Act (NIA), a set of six statutes passed between 1790 and 1834 that aim to regulate commerce between non-Native and Native governments. HR 1532 zeroes in on the Nonintercourse Act’s requirement for federal consent on the sale of fee lands held and potentially sold by tribes.

“The NIA was designed to prevent tribes from being defrauded, but today it interferes with the ability to encourage normal business activities for tribes that are eminently capable of making their own business decisions,” Osceola told the committee. “We…urge Congress to move quickly to enact HR 1532.”

Osceola said the NIA had nearly stifled the Seminole Tribes’ real estate efforts by preventing insurance companies from insuring mortgage liens due to concerns about the legislation. The industry-wide refusal to insure liens brought the tribes’ real estate plans to a “grinding halt” until one insurer decided to take a risk and provide insurance.

Legislation introduced by Florida Sens. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) and Rick Scott (R-Fla.) that eventually became Public Law 117-65 helped the Seminole overcome the issue.

“The sustainable economic independence of the Seminole tribe or any other federally recognized tribe should not depend on one title company's willingness to provide title insurance to lenders or buyers without the act of Congress,” Osecola said. “That law gave the Seminole Tribe the opportunity to shop carriers and lenders and have the confidence to continue to acquire real estate investments.”

During his testimony, Williams said the NIA’s provision regarding federal consent for the sale of simple fee land might have once been necessary, but now hindered tribes’ ability to do business. Tribes trying to sell off-reservation property find themselves forced to seek legal permission from the Department of Interior or seek legislative relief from Congress — both lengthy processes that create huge risks for new enterprises or businesses.

Williams pointed, by way of example, to an ongoing conflict between the Interior and the United Auburn Rancheria, who have been attempting to sell a public golf course on fee land that the tribe acquired in 2012. The title company involved in the transaction is unwilling to provide insurance until the Interior has provided a legal opinion clearing the land from the NIA, Williams said.

The arrangement regularly creates legal tangles that could be solved with blanket legislation - acknowledgements that have already been extended carte blanche to several tribes across the country, Williams noted.

“Over the past two decades, Congress has passed NIA waivers for specific tribes in Florida, Oregon, Oklahoma, Minnesota and Michigan,” Williams said. “However, instead of adopting a tribe-specific approach to curing this problem, HR 1532 addresses this issue for all federally recognized tribes and avoids the need for Congress to continue to pass legislation for individual tribes. For all these reasons, United Auburn strongly supports HR 1532.”

Newland expressed opposition to the bill on the grounds that it could create “confusion” around an array of case law and precedent built on the existing interpretations of the NIA and “inadvertently harm tribes in the process,” he told the committee.

While HR 1532 doesn’t directly amend the NIA, it could muddy the waters surrounding what the law means for Indian lands, Newland said. He conceded that the constant requests for approval by commercial lenders and title holders created an “unnecessary step” for tribal transactions, but that the legislation was itself unnecessary.

“It’s a solution in search of a problem,” Newland told the committee in response to a question about the “reaction” from title and lending institutions to potential NIA complications. “The department doesn’t dispute that this is an issue…but [these institutions’] attorneys need to take an Indian law class.”